The Mystery of the Crucifixion and Resurrection of Jesus: His Triumph over the Physical Laws of Earthly Realities

by sprincipe2012

All photos from Wikipedia

In this paper I shall examine how the Gospel writers, via the recollections of his disciples, reported the discussion that emerged from Jesus’s opening question: “Who do people say that I am?” (Mark 8:27, based on Peter’s recall of Jesus’ sayings). Some among Jesus’ followers may have regarded their master as the “Son of the living God.” Jesus preferred to call himself “the Son of Man;” in Matthew 16:13 he asks, “Who do people say that the Son of Man is?” This is symbolically related to Jesus’ reading of Daniel 7:13-14. The Old Testament visionary had prophesied that “one like a human being coming with the clouds of heaven…[will be] presented to the Ancient One.” Jesus re-phrased these lines when he appeared before the High Priest Caiaphas at Jerusalem (Matthew 26:64).

How did Jesus arrive at his thoughts upon the Son of Man, who according to Daniel 7:14 would inaugurate a new “everlasting dominion that shall not pass away”? Unexpectedly to all – maybe even to Jesus himself – Jesus was resurrected from the dead through the Godhead’s miraculous intervention. In his extraordinarily exalted spiritual being, he embodied Genesis 1:26, in which God said: “Let us make humankind in our image.” Ezekiel 1:26 describes “something like a throne, in appearance like sapphire; and seated above … something like a human form.” Altogether, Jesus’ resurrected “Being” attested to the ennoblement, even the sanctification, of his earthly humanity, and especially his sufferings.

Jean Danielou, imagining that earth angels would have accompanied Jesus back up to heaven during his “Ascension” – suggests that a great “mystery” was revealed to the greatest angels in heaven. Once Christ arrived there, still bearing the disfigurements of his wounded, bleeding body, the heavenly orders could not readily understand at first: why were they called upon to bow down to this human being in his stricken state? Danielou declares:

The Ascension is not only the elevation of Christ in His Body into the midst of the angels; to be more theologically precise, it is the exaltation of human nature, which the Word of God has united to Himself, above all the angelic orders which are superior to it.[1]

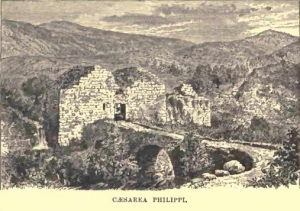

In addition to considering Jesus’ heavenly state, I would like to explore some psychological considerations regarding what the human being, Jesus, had to go through during his final days on earth. Without any disrespect for the divine dignity of Jesus the Christ, I shall treat this discussion of his humanity as though I were once again among the clinical staff at the psychiatric hospital where I worked as a social worker for many years. If we had been asked to assess what was happening with this person, Jesus, let us say, from the time when he told his disciples at Caesarea Philippi that he would be killed in Jerusalem (but rise again), until his actual crucifixion, we would be restricted, of course, to the Gospel accounts by Matthew, Mark, Luke and John, which were all based on tradition handed down by his closest disciples. Nevertheless, the events in Matthew, Chapter 16, if faithfully recorded, are very revealing of what was going through Jesus’ mind while he contemplated the uncertain future of his mission.

Can we glean insights into what was apparently going on in Jesus’ mind while he was staying in the north near Caesarea Philippi? From Matthew’s account alone, there is sufficient evidence to claim, as I suggest, that Jesus himself did not know ahead of time exactly how the Godhead would bring about his resurrection, or how a new spiritual kingdom was possible on earth. What he realized, however, was that he would definitely have to face the religious authorities at Jerusalem where, very likely, he was going to die.

Carrying His Cross: Matthew 27: 27-32

Let us begin with the sight of the man, Jesus, carrying his cross. He would have felt a profound despair, exceedingly vulnerable to all the ills heaped upon him, and extraordinarily anxious, even hopeless. We can suppose that many people in Jerusalem witnessed Jesus carrying his heavy wooden cross to Calvary, today the site of the Church of the Holy Sepulcher. In those days, it was a stone-quarry just outside the city, presumably where stones were cut for building the Temple.

The Roman soldiers had obeyed Pontius Pilate’s judgment against Jesus: at he was a threat to order in Jerusalem. They stripped Jesus of the decency of clothes, and whipped his body without mercy. Mocking him who had been acclaimed “King of the Jews” by the crowds on Palm Sunday, they wound thorn branches around his head to form a mock “crown.”

To a psychologist, the crown of thorns is more than mere cruel and ironic symbolism. It projected onto the personhood of Jesus the perplexity and confusion in the minds of the authorities, particularly Pilate, who had ordered the execution of this seemingly innocent individual for having declared “his kingdom was not of this world” – the meaning of which was not clear.

A week before his crucifixion, on Palm Sunday, many of those in Judea, having heard that Jesus had raised more than one person from the dead, laid down palm branches (among the Jews, a symbol of victory or triumph) in his path as he entered Jerusalem riding on a donkey. Was this a kind of idolatry? At the very least, in paying such honor to Jesus, who had demonstrated his “triumph” over the death of others like Lazarus, they would have remembered Zechariah’s lines of prophecy, signifying Jesus’ potential candidacy for kingship. Zechariah9:9 (which Matthew 21:5 later repeated):

Rejoice greatly, o daughter Zion! Shout aloud, O daughter Jerusalem! Lo, your king comes to you; triumphant and victorious is he, humble and riding on a donkey, on a colt, the foal of a donkey.

Jesus must have felt truly “humble.” He must have been well aware that his acclaim by the crowd would lead to the authorities noting his popularity, and he must have been reminded that the most powerful people in Jerusalem were capable of sentencing him to death.

Less than a week later, the Roman soldiers, obeying Pilate’s order to crucify Jesus, compelled him to carry his cross through the streets using a route – now known as the Via Dolorosa – that winds through the Old City of Jerusalem. We can suppose that the witnesses to this event would have been shocked into silence as they contemplated the Romans’ infliction of this most cruel punishment. And more so, as they witnessed what a physical struggle it was for someone whose physique was lean and perhaps frail from his meager diet and frequent fasting. At one point, Jesus fell down, and the soldiers impressed another stronger person, a man from Cyrene, into bearing the cross in Jesus’ stead.

We can speculate further that the burdensome cross Jesus carried was more than just beyond his physical strength. Did he bear a crippling sense of failure in having been unable to inspire the Pharisees, Saducees and scribes among the Jerusalem elite with his teachings about “the living God”? If the one whom he called his “Father in Heaven” was really a “living God,” still among them, then his greatest anxiety would have been: would his prayers to be resurrected be answered after his certain death on the cross?

Matthew 26: 36-46. Jesus Prays in the Garden of Gethsemane

We can well imagine what a terrible night Jesus endured before he was to be crucified the next day. He was praying in the Garden of Gethsemane on the lower slope of the Mount of Olives, alone in the darkness of night because his chosen companions, Peter and the two sons of Zebedee, James and John, had succumbed to sleep. He must have felt abandoned by even these closest friends. Earlier, he had appealed to them: “I am deeply grieved, even to death; remain here, and stay awake with me.” At one point, he tried to wake them, exhorting them: “Stay awake and pray that you may not come into the time of trial.”

We can well imagine what a terrible night Jesus endured before he was to be crucified the next day. He was praying in the Garden of Gethsemane on the lower slope of the Mount of Olives, alone in the darkness of night because his chosen companions, Peter and the two sons of Zebedee, James and John, had succumbed to sleep. He must have felt abandoned by even these closest friends. Earlier, he had appealed to them: “I am deeply grieved, even to death; remain here, and stay awake with me.” At one point, he tried to wake them, exhorting them: “Stay awake and pray that you may not come into the time of trial.”

The time of trial, of course, awaited Jesus, who was about to be brought before the chief priests and elders, and the governor Pilate. His subsequent words to his disciples, whom he could not keep from their slumbers, spoke to his own sense of personal weakness at that moment: “the spirit is willing, but the flesh is weak.” Could he go through with the awful fate awaiting him?

Has it happened to you, dear reader, that on the night before some terrible event takes place, whether consciously anticipated or merely sensed as premonition, sleep will not come – only disturbing thoughts? As Matthew 26:37 described Jesus, at that time, he “began to be grieved and agitated.” Normally, Jesus was as sane and composed a personality as anyone, not given to emotional weakness or mental struggle. However, Jesus could not help dwelling on the pain and humiliation he knew he would have to withstand the following day. Although he had predicted to his disciples more than once that such things could happen – that he was going to be condemned to death by the authorities – now he would have to experience the imposition of Roman crucifixion in reality–an awful and shameful end to any person’s mortal life.

At Caesarea Philippi: Matthew 16:21-28

(Recalling Ancient Nature-De)

Let us go back to when – according to Matthew, Mark , and Luke –his disciples first received evidence that Jesus sensed the events to come in Jerusalem. Matthew 16 provides a sequence of seed-ideas that Jesus must have noticed at that time. Matthew (16: 24-28) suggests that Jesus knew he would later have to carry his cross in Jerusalem, and Matthew connects this knowledge with what Jesus said at Caesarea Philippi: that anyone who wished to follow him would have to: “…deny themselves … take up their cross and follow me.”

Let us go back to when – according to Matthew, Mark , and Luke –his disciples first received evidence that Jesus sensed the events to come in Jerusalem. Matthew 16 provides a sequence of seed-ideas that Jesus must have noticed at that time. Matthew (16: 24-28) suggests that Jesus knew he would later have to carry his cross in Jerusalem, and Matthew connects this knowledge with what Jesus said at Caesarea Philippi: that anyone who wished to follow him would have to: “…deny themselves … take up their cross and follow me.”

Matthew 16, Mark 8, and Luke 9 all record a similar version of the conversation that Jesus holds with his disciples when they are alone at Caesarea Philippi. Matthew 16:13 tells us that “when Jesus came into the district of Caesarea Philippi, he asked his disciples: ‘Who do people say that the Son of Man is?’” As mentioned, this term “Son of Man” corresponds to Daniel 7:13. These specific lines of Scripture were to form the basis of Jesus’ theological defense before the High Priest in Jerusalem, and that would frustrate Caiaphas greatly. Matthew locates this conversation in the neighborhood of Caesarea Philippi, over which the great Mount Hermon stands as a landmark, close to the modern Israeli border with Lebanon and Syria. The snow-capped and cloud-covered Mount Hermon may have served as landscape symbolism for Daniel’s vision of one coming down on the clouds of heaven (Dan. 7:13).

One can only wonder if Jesus knew, while staying at Caesaria Phillipi, that he could face crucifixion at Jerusalem, considering the theological tensions among the different priestly groups established there. His conversation with the disciples might be understood as his asking of this possibility: “What if….?”

While thinking this possibility through, he assimilated past religious traditions associated with Mount Hermon, the great mountain which likely informed Daniel’s vision of the Son of Man arriving on the clouds of heaven, and which would have been believed to house the “Ancient of Days” (a mountain god, or supreme being, metaphorically compared to the antiquity of such great mountain ranges (Dan. 7:13-154)). Thus, here Jesus prepared all the ideas, drawing from Daniel, which he would evoke during the week before his crucifixion in Jerusalem.

In the 1st century CE, the Judean Tetrarch, Philip, built a city here to honor the Emperor Augustus, likely in view of the natural beauty surrounding Mount Hermon. The mountain had always attracted nature-lovers, especially the popular religious cults of ancient nature-deities. Traditionally, it was a place where people built temples: in Hellenist times it was a sanctuary for the Greek god Pan, and much earlier, a temple for the Canaanite storm god featured in the Late Bronze Age texts discovered in 1929 at ancient Ugarit in Syria. Did Jesus find inspiration from this setting for his thoughts upon Daniel 7:13-14; and in regard to his thoughts on Daniel 7:2-10, did he consider earlier kingdoms which had extolled nature deities and which had by then been largely forgotten?

Today, Druze Muslims live in various towns and villages around the slopes of Mount Hermon. One of those towns, situated very high up on the mountain, is usually wrapped in clouds that drift over the streets. My daughter Concetta and I visited this unusual cityscape enveloped in clouds in 1996, on a bus tour of the north of Israel. Further down at the foot of the mountain, Concetta and I enjoyed the freshness of the air in these natural settings. There is a small waterfall (“Banias’ Waterfall,” the Arabic form of the Greek “Pan,”). Nearby in a small pool surrounded by flowers, they have placed a stone sculpture of Pan. One descends stone-steps into a small gorge where a waterfall pours down into a rushing stream, and the branches of a large old tree overhang this refreshingly cool spot. “It’s like being back in Canada,” I told Concetta.

Jesus traveled into the district of Caesarea Philippi to spend time in this natural beauty, where he could relax and be at ease with his disciples. One supposes that his thoughts began to flow further ahead after the significant encounter he had just had with some Pharisees and Saducees in the same district. Matthew 16:1-4 records that they had asked him “to show them a sign from heaven.” Were they testing Jesus according to the reputation he had already gained as a wonder-worker, or perhaps as a prophet?

Recalling Elijah’s Miracles from God – The Transfiguration

Matthew 16:13-16, tells us that while relaxing in this intimate circle of trusted friends at Caesaria Philippi, Jesus ventured to ask of them: “Who do people say that the Son of Man is?” The disciples spoke of the Baptist, Elijah, Jeremiah and other prophets, without thinking very hard about his question. After all, what did they know of what he had in mind? But, Peter thought hard before answering Jesus’ next question, “Who do you say that I am?” Peter answered: “You are the Messiah, the Son of the living God.” (Note that Mark 8 and Luke 8 use the term “Messiah,” but not the “Son of the living God” as in Matthew; likely, Matthew was referencing the ancient Israelite prophet, Elijah)

Mark 9 tells of Jesus’ encounter with Elijah and Moses on another high mountain in the Galilee. One wonders whether, because Jesus was thinking hard about his disciples’ answers, he became determined to seek out the prophet, Elijah, along with Moses, to discover more about his mission. Mark, 9:1-7, recounts that the disciples Peter, James and John saw Jesus at the top of the mountain and that he was: “transfigured before them, and his clothes became dazzling white, such as no one on earth could bleach them.” Later, “a cloud overshadowed them [Jesus was sitting with Moses and Elijah], and from the cloud there came a voice, ‘This is my Son, the Beloved; listen to him.” What Jesus talked about with Moses and Elijah, we do not know.

On his way down the mountain Jesus held a conversation with the disciples. He answered questions regarding “the meaning of rising from the dead,” and the scribes’ pronouncement that “Elijah must come first” (this references Malachi 4:5:“Elijah would come before the great and terrible day of the Lord”). Jesus gave the following explanation, which along with his other comments must have raised more questions in their minds.

Elijah is indeed coming to restore all things. How then is it written about the Son of Man, that he is to go through many sufferings and be treated with contempt? But I tell you that Elijah has come and they did to him whatever they pleased. (Mark 9:11-13)

Presumably, when Jesus refers to Elijah having come, he meant for John the Baptist to stand in for Elijah. To return to Matthew 16:21, we learn that, at Caesaria Philippi, Jesus started to prepare his disciples for what was coming: he was not going to become a king of Judea, but would undergo great sufferings in Jerusalem at the hands of the elders and priests. He would be killed, but “on the third day he would be raised.”

Where did such an idea come from? Another ancient prophet of the northern Kingdom of Israel, Hosea, comes to mind. He called the people to repentance in the 8th century BCE:

Come, let us return to the Lord: for it is he who has torn, and he will heal us; he has struck down, and he will bind us up. After two days, he will revive us; on the third day he will raise us up, that we may live before him (Hosea 6:1-2).

Hosea’ prophecies suggest that his nation would recover when, after Hosea’s death, the Assyrians would destroy the Northern Kingdom. But miracles happened for individuals whenever Elijah prayed earnestly to God. There is the story of the woman who gave Elijah bread to eat when he was famished; and later, Elijah was able to bring her son back to life through his fervent prayers. Jesus manifested similar miracles, feeding five thousand with loaves and fishes, and bringing some people back to life from their fatal illnesses.

The episode at Caesarea Philippi, in Matthew 16:1-4, implies what Jesus must have been thinking after his encounter with some Pharisees and Saducees whom he met in the north. The Pharisees believed in the “Resurrection of the Dead in the Last Days,” a belief influenced by the prophecy of Malachi 4:5; the Saducees, however, did not subscribe to such beliefs. In Malachi 4, the prophet had said that for those who revere the name of the Lord, “the sun of righteousness shall rise, with healing in its wings. You shall go out leaping like calves from the stall” (Mal. 4:2).

Was Jesus wondering if – since “Elijah had already come” in the person of John the Baptist, and had been executed by the Herodian Tetrarch – “the Day of the Lord” was at hand? What did this mean for the Pharisees’ apocalyptic beliefs, that the resurrection of the dead would take place “in the last days”? Jesus criticized both the Pharisees and Saducees for not being able to interpret “the signs of the time,” saying further, “no sign will be given except the sign of Jonah.” In mentioning Jonah, Jesus would have been thinking of the prophet swallowed by a whale. Following upon Jonah’s desperate prayers to the Lord, the whale cast Jonah up onto the beach – “after three days.”

After his speech with the Pharisees and Saducees, Jesus warns his disciples to beware of “the yeast of the Pharisees and Saducees,” referring to their teachings; this metaphor was to remind them of the five loafs of bread that fed the five thousand (Matthew, 16: 5-12). Here, Jesus emphasizes the great importance of holding to faith in God’s miraculous powers. One thinks Jesus was beginning to realize he would need a miracle from God when facing a judgment by the authorities at Jerusalem.

Jesus would have been well acquainted with the stories about the miracle-worker, Elijah, particularly 1 Kings 17: 8-16. The Lord directed Elijah to go to a town called Zarephath, belonging to Sidon, a city in Phoenicia. There he would find a widow who would feed him. Sadly, the woman tells Elijah she had only enough flour and a little oil left to make a little cake for her son and herself; then they would die in the famine that was gripping the land. Elijah, testing her, asks that she first make a little cake for himself. Then he assures her that the Lord God of Israel would insure the jars of flour and oil would never be empty so long as the famine lasted. She does as requested and they all eat until the end of the famine.

Later, in 1 Kings 17:17-24, while Elijah is still staying at the widow’s house, her son dies. Elijah carries the boy up to his own bed and lays his own body on the boy, crying out to the Lord to let the boy’s life come back again, and the child is revived. Then the woman says to Elijah: “Now I know that you are a man of God, and that the Word of the Lord in your mouth is true.”

One thinks Jesus may have had a habit of repeating to himself the woman’s words to Elijah, but silently. The Lord God had called Jesus his “beloved son” at his baptism in the Jordan, and then again during his transfiguration on the mountain in Galilee. Nevertheless, Jesus continued to speak of himself as “the Son of Man” (certainly not “the Messiah”). Was that because he feared being accused of blasphemy by the religious authorities, or perhaps in contravention of the scriptural prohibition against “prophecy”?

Jesus’ Thinking Transcended Earlier Religious Traditions

The post-Exilic Prophet known as “the Second Zechariah” proclaimed in the 5th century BCE:

If any prophets appear again, their fathers and mothers who bore them will say to them, you shall not live, for you speak lies in the name of the lord; and their fathers and mothers who bore them shall pierce them through when they prophesy. (Zech 13:2-6)

Part of the problem with acknowledging Jesus as “Messiah” – or even as a man of God like Elijah, or as “the Son of the living God” as Peter called him – lay in the above Scriptural warning. It would have been highly consequential if “the Day of the Lord,” as prophesied by Malachi and Zechariah, was coming soon. Perhaps Jesus’ claim before the High Priest Caiaphas that, “From now on, you will see the Son of Man coming on the clouds of heaven,” sounded too much like someone assuming the role of prophet.

Jesus, knowing he would have to face death in its different forms, foretold a few times that, nevertheless, he would arise again. Where else did such an idea of the “resurrection of the dead” come from – outside of the Hebrew Scriptures, that is?

In the afore-mentioned Ugaritic texts, as translated by Ringgren,[2] Baal dies as a result of an encounter with the god of death, Mot: “Baal has fallen to the ground, Al’iyan Baal is dead, the prince, lord of the earth has perished.” (Anchor Bible VI, 8-10)

On hearing this, El goes into mourning, rolls in the dust and tears his clothes. Ringgren fills us in on how the sun-goddess carries Baal’s body back, and afterwards Baal’s sister Anat “buries him up in the north with rich funeral offerings.” Part of the succeeding text is lost, but then, the following passage (1 AB III-IV, 5-9) appears. El has a dream, though it is uncertain who is telling of El’s dream:

In a dream, O El the gentle, in a vision, O creator of the creation,

the heavens rained fatness, the streams flowed with honey.

I know that Al’iyan Baal lives, that the prince, lord of earth, exists.

A psychologist would interpret the ancient Canaanites’ deification of the powers of nature – such as with the rain-bringer, Baal – as people projecting their hopes, fears and dreads onto a mythical being. The ancient pagans, who erected temples to this unpredictable deity, must have lost their faith at times, particularly whenever the forces of Nature turned against them – which they would interpret as re-enacting the times of drought after Baal died at the hands of Mot.

In Jesus’ vision of his future resurrection, as he describes it at Caesarea Philippi, it would not be like the growth of nature in the springtime, with Baal’s earthly kingdom transformed. If his Father in Heaven was going to resurrect him from the dead, such a great heavenly miracle would transform the meaning of the Pharisees’ belief in the resurrection of the dead in the last days – since that would mean they, without knowing it, were living in the last days of Judea. But Jesus’ resurrection would not be like Lazarus coming back to physical life, evoked by the prayers of Jesus. Jesus’ resurrection would take a spiritual or “heavenly form,” as mysterious as the power of his Father in Heaven to re-create the earthly so as to resemble more closely a celestial Being.

Jesus was Destined to Die at Jerusalem

While the Jerusalem Temple still stood in Jesus’ time, it served as the center of the Judaic cults. Daniel, however, had foreseen (8:13-14) that the time would come when the sanctuary would be “made desolate … unable to be restored to its rightful state.” This did come about in 70 CE when the Romans burned and demolished the Temple, which apparently Jesus foretold, saying, “not a stone will be left unturned.” And these words were repeated during his trial, condemning him for this baleful prediction.

But, while the Temple still stood, the High Priest (Caiaphas in Jesus’ time) was permitted to enter the Holy of Holies on one day of the year, the Day of Atonement during the Festival of Trumpets. Then, he was able to address prayers to the Most High to forgive the sins of the people from the preceding year. Thirty some years after Jesus’ crucifixion, the temple was destroyed by Roman forces, and the priestly sacrificial cults necessarily came to an end. Jesus, meanwhile, had joined his father in Heaven. Thus, it could be said that Heaven ordained that Jesus, sent to Jerusalem to die, would rise again as a new kind of heavenly priest (according to the order of Melchizedek, Hebrews 5:6), to whom people could pray to be forgiven of their sins – needing neither temple nor priestly cult.

At the moment of Jesus’ death on the cross, Matthew 27:51 says: “the curtain [veiling the Holy of Holies] of the temple was torn in two, from top to bottom.” This was symbolic of the Temple’s forthcoming destruction.

Jesus’ Speculations regarding his Future Resurrection

Jesus said to his disciples (Matthew 16:27) that, “some standing here will not taste death before they see the Son of Man coming in his kingdom.” He repeated these mysterious words again and again, but at the time nobody could understand this prediction.

One could speculate that, while Jesus tarried at Caesarea Philippi during his holiday, he arrived at some of his thinking about what was to happen to Judea “after the Day of the Lord”(the future war with Rome), particularly in regard to the Jerusalem Temple.

“Simon Peter, son of Jonah” (Matt. 16:16-19), as Jesus addressed his disciple, recognized him as “the Son of the living God.” Jesus’ response came as a promise, or a prophecy: “you are Peter, and on this rock I will build my church…. I will give you the ‘keys of the kingdom of heaven.’” This is just as Elijah had given his mantle to his follower Elisha before Elijah ascended to heaven. Thus, the New Kingdom, which became the Christian Church, was founded on the insight of this disciple, Simon, son of Jonah, whom he renamed “Peter,”meaning the “Rock”(his English name deriving from the Greek Petrus, or Cephas in Hebrew).

When Jesus’ thoughts turned to Jonah, who had been forced to spend three days in the belly of the whale, Jonah’s metaphorical liberation from the whale spoke to Jesus of his resurrection to come, “after three days” of death. Later, in Matthew 26, 61, there is the report by two witnesses, at Jesus’ trial before Caiaphas, that Jesus had asserted: “I am able to destroy this temple of God and to build it in three days.” If Jesus did say this, it must have been uttered in the voices of his accusers as an actual prophecy that a newly Anointed one, the Christ, would build a Church – “not of stones,” but of “Faith.”

After Jesus arrived in Jerusalem, and in line with Hebrew prophets of old, out of his mouth came castigations, e.g. Matthew 23:13: “But woe to you, scribes and Pharisees, hypocrites! For you lock people out of the kingdom of heaven.” One thinks that when Jesus took issue with the Sadducee priests in charge of the temple, in Matthew 23:16-22, it was because “some,” he said, were telling people to swear an oath by “the gold of the sanctuary,” and not by the sanctuary itself. In the same diatribe against religious hypocrites, he referred to the Pharisees decorating the graves of the righteous. They were in the habit of saying: “If we had lived in the days of our ancestors, we would not have taken part with them in shedding the blood of the prophets” (Matt. 23:29-30). Yet, they would be among the elders concurring with slaying the new prophet who had come among them.

Reading Matthew 23, a clinically-minded modern psychologist might suppose, if they knew little else about Jesus as a prophet in the Hebrew tradition, that here he was expressing the utmost emotional frustration at being unable to convey his teachings about the “living God” – particularly to those professing such belief as dogma. He was teaching this not as the faith in which they lived – either within the temple like the Saducees, or without, like the Pharisees – but was always harking back to the Maccabean ancestors whose graves they honored.

Do you not see, dear reader, that now Jesus was heading on a downward path – in effect, he was intent on self-destroying the identity ascribed to him by his followers on Palm Sunday: that he was a kind of “King-Messiah.” One can interpret that, mentally, he was proceeding towards his crucifixion – by which he hoped to be able to “crucify” his own physical body and blood. He was going to place all his hopes and faith in the higher power of the Living God, his Father in Heaven. But, he did not know for certain how this would turn out. The Gospel-writer, John, later interpreted the consequences of Jesus’ resurrection. For John, it meant that:

To all who received him [Jesus], who believed in his name, he gave power to become children of God, who were born, not of blood or of the will of the flesh or of the will of man, but of God (John 1:12-13).

The Beggar at the Gate, Lazarus

The New Revised Standard Version of the Bible introduces the Gospel-writer Luke as showing a special interest in social outcasts such as women and the poor, with reference to three well-loved stories told by Jesus that are only to be found in Luke’s narrative: the good Samaritan, the prodigal son, and the tale of Lazarus. Luke opens the chapter containing the parables of the prodigal son and “the rich man and a beggar named Lazarus” by describing that, as the “tax collectors and sinners” gathered around Jesus, the Pharisees and scribes scoffed at Jesus’ companions, who were outcasts, to be sure. It appears that the story of Lazarus was told for the benefit of the strictly religious Judeans, who too often showed little heart and compassion.

Jesus described a poor man named Lazarus, hungry and covered with sores, who sat by the gate hoping for any food left over from the rich man, who “feasted sumptuously every day.” When the poor man died, the angels carried him away to be with Abraham. But when the rich man died, he ended up in Hades, “in agony with these flames.” Abraham spoke to him of the “chasm” between himself and Lazarus (which we speak of today as the growing gap between the rich and the poor). When the rich man begged that his living brothers be fore-warned, Abraham said to him: “If they do not listen to Moses and the prophets, neither will they be convinced even if someone rises from the dead.”

When Jesus entered Jerusalem for the last time, where he would sleep in the open on the slopes of the Mount of Olives, he may have felt like Lazarus, the beggar at the gate. He would receive no welcome in the city from its worthiest citizens, the Pharisees and temple priests. Initially Jesus received the accolades of many followers on Palm Sunday, but then, after observing Passover with his followers during his Last Supper on earth, he was betrayed, just as he had foretold in Matthew 20:18-19:

The Son of Man will be handed over to the chief priests and scribes, and they will condemn him to death; then they will hand him over to the Gentiles to be mocked and flogged and crucified; and on the third day he will be raised.

“Lazarus, Come out,” the Gospel of John

As the Gospel of John (Ch. 11) narrates, not long before Jesus traveled to Jerusalem for Passover, while staying at Bethany-beyond Jordan, news came to him of the death of a different Lazarus, brother of Martha and Mary. They lived in the town of Bethany in Judea, near Jerusalem, and Jesus was ready to go there, even though, according to John 11:7-8, his disciples warned him that the religious leaders in Jerusalem had wanted to stone him. Jesus reassured them by saying, “Our friend Lazarus has fallen asleep, but I am going there to awaken him.” John quotes Jesus: “Lazarus is dead. For your sake I am glad I was not there, so that you may believe.”

Jesus found Martha and Mary weeping, and blaming him for not having been there to save their brother. At this point, the Gospel of John records the conversation that Jesus had with Martha – regarding her belief in the “resurrection on the last day.” He declared to her: “Your brother will rise again,” along with the mysterious words, from John 11:25:

I am the resurrection and the life. Those who believe in me, even though they die, will live, and everyone who lives and believes in me will never die.

Whether Jesus said these words or not, John took this opportunity to express his own belief in Jesus as “the resurrected one.” Before he called upon the dead Lazarus to arise and walk of his tomb, Jesus is described as “disturbed,” and having wept, he prayed to the Father and then called: “Lazarus, come out.”

One thinks that Jesus, identifying so closely with those who had recently died, such as Lazarus, suffered greatly with anxious fore-bodings of his coming death, hoping beyond hope that his Father in Heaven would give him back his life – somehow. But, there was no certainty of this. Jesus, praying to God in the midst of his grief for the loss of his friend Lazarus, expressed a prayer that was as much for himself as for his friend. At the same time, was he not also feeling, as I’ve suggested, much like the other Lazarus – the beggar at the gate – socially and religiously unacceptable to the elites at Jerusalem?

Jesus’ Crucifixion and Resurrection

Before Jesus uttered his final words on the cross, crying out to God, “why have you forsaken me?” (Mark 15:34), he must have sunk into deep despair, utterly defeated by his failure to influence the religious leadership of the Pharisees, Saducees and scribes. Before the high priest, elders and scribes, in Mark 14: 61-62, asked him: “Are you the Messiah, the Son of the Blessed one?” Jesus did not respond to this title.His actual words seemed nonsensical tothe high priest,who tore his clothes in frustration andthen concluded Jesus’ speech was blasphemy. As mentioned, Jesus claimed, according to Matthew 26:64, to be the one envisioned in Daniel 7:13-14, saying to an august assembly of religious rulers over Judea: “You will see the Son of Man seated at the right hand of the Power, and coming with clouds of heaven.” At Jesus’ trial before Pilate, according to Mark 15:5, he had nothing to say. Clearly, Jesus wanted to convey his elevated faith in the power of the Godhead only to the High Priest of the Jews.

Regarding the charge by some that Jesus thought of himself as “the king of the Jews,” the Gospel of John, 18: 36, quotes Jesus as saying to Pilate: “My kingdom is not from this world.” This is possibly the most important idea in all the Gospels accounts of Jesus – whether Jesus actually said these words, or not. After Jesus died on the cross, his followers pleaded for his body, which they placed in the rock-cut tomb of a rich man, wrapping him in a burial shroud, and closing the tomb with a great-sized stone. But, Jesus did not die.

The Gospel of John’s “My kingdom is not from this world” more closely approaches the truth of Jesus’ resurrection, not back to physical life, but as a new kind of miracle manifested by God. The “spirit” or “soul” of Jesus, which had always given praise to his Father in Heaven became, after his physical death, united with the Godhead as the becoming of a New Spiritual Reality.

As Jesus had said to Martha, all souls who would aspire to a union with the heavenly Father could gain an eternal life in God’s heavenly kingdom. This made sense at the symbolical level of what Jesus said to the high priest, quoting Daniel 7:13, that he would fulfill the prophecy of “the Son of Man on the clouds of heaven.” The last verse of Daniel 7:14 described one like a “human being” on the clouds of heaven, who would receive “an everlasting dominion that shall not pass away, and a kingship that shall never be destroyed” (Daniel 7:14). Jesus understood that this did not refer to an earthly kingdom.

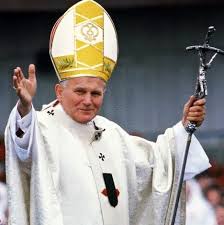

The Resurrection of Jesus According to Pope Benedict XVI.

Pope Benedict XVI, as Joseph Ratzinger, explains Jesus’ resurrection from the sead in his book Jesus of Nazareth.[3] In his introduction Benedict says that if the truth that Christ arose from the dead were taken away, while it would still be possible to put together some interesting ideas about God and humankind – “the Christian faith would be dead… Jesus would be a failed religious leader, who despite his failure remains great and can cause us to reflect.”

As Benedict points out, Jesus did not return to a normal physical life like his friend Lazarus. His rising from the dead did not represent “the miracle of a resuscitated corpse,” as in the examples of the widow’s son at Nain, who stood up from his funeral bier at Jesus’ touch (Luke 7:11-17), or the daughter of Jairus, leader of a synagogue in Galilee (Mark 5:22), to whom Jesus said: “Little girl, get up.” Nor, Benedict says elsewhere (2011:273), was Jesus simply a “ghost (‘spirit’)” – belonging to the realm of the dead, but revealing himself to the living. [4]

Benedict asserts that the disciples’ encounters with their risen Lord were not the same as “mystical experiences,” during which the human spirit is temporarily “drawn aloft out of itself.” Paul described his elevation to the third heaven, but distinguished that experience from the encounter with Christ on the road to Damascus.

At least temporarily, Jesus took on a form of physical embodiment when, for instance, he appeared to Mary Magdalene in the garden (John 20:17), cautioning her: “Do not hold me, for I have not yet ascended to the Father.” After rising from the dead, Jesus appeared to the disciples on different occasions in his as yet un-ascended, heavenly form. He walked with two of them on the road to Emmaus; he stood on the shore of Lake Galilee inviting his disciples to eat some fish with him. At first, they did not recognize Jesus, their “Lord;” Benedict says: [BLOCK]

His presence is entirely physical, yet he is not bound by physical laws, by the laws of space and time. In this remarkable dialectic of identity and otherness, of real physicality and freedom from the constraints of the body, we see the mysterious nature of the risen Lord’s new existence. …. He is the same embodied man, and he is the new man, having entered upon a different manner of existence. [5]

For Benedict[6] Jesus’ Resurrection spoke of “something outside of our world existence.” He says further, “a new dimension of reality is revealed… If there really is a God, is he not able to create a new dimension of human existence, a new dimension of reality altogether?” In this regard, Benedict quotes Paul (2 Corinthians 5:16-17), who understood this as follows:

Even though we once regarded Christ according to the flesh, we regard him thus no longer. Therefore, if anyone is in Christ, he is in a new creation.

As for Jesus’ Ascension (Acts 1:6-8), according to Benedict, when Jesus disappeared into the cloud, this did not mean he was taken to some other cosmic location. It meant, rather, that he was taken up into “God’s very being, participating in God’s powerful presence in the world.”[7]

[INSERT IMAGE-benedict]

In conclusion, one can suppose that Jesus’ total being was more purified and perfected than any other person we might think of. At the same time, I can understand the imaginative description by Jean Danielou of Christ arriving in heaven – still wearing his blood-stained garments and flesh-wounds – because this Christened one would not have disdained these marks of Jesus’ origins in suffering humanity.

Jesus’ resurrection from the dead in his spiritual body remains, to some, merely a myth. Nevertheless the immortalized remains of the saintly dead, the incorrupt bodies of the occasional few among us, are visible signs still present today of the triumph of the spirit/soul over physical death. [8]

[1]Jean Danielou. According to the Fathers of the Church: The Angels and Their Mission, translated from the French by David Heimann. Westminister, Maryland: the Newman Press, 1957. P. 56.

[2] Ringgreen, Helmer. Religions of the Ancient Near East. SPCK Publishing; First Translated Edition edition (January 18, 1973). P. 149.

[3] Ratzinger, Joseph, Pope Benedict XVI. Jesus of Nazareth (Part Two): Holy Week from the Entrance into Jerusalem to the Resurrection. English translations by the Vatican Secretariat of State, San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 2011. P. 241-277

[4] Ratzinger. P. 243.

[5] Ratzinger. P. 266.

[6] Ratzinger. P. 247

[7] Ratzinger. P. 287.

[8] Joan Carroll Cruz. The Incorruptibles, A study of the Incorruption of the Bodies of Various Catholic Saints and Beati. Rockford, Illinois: Tan Books and Publishers, Inc, 1977..